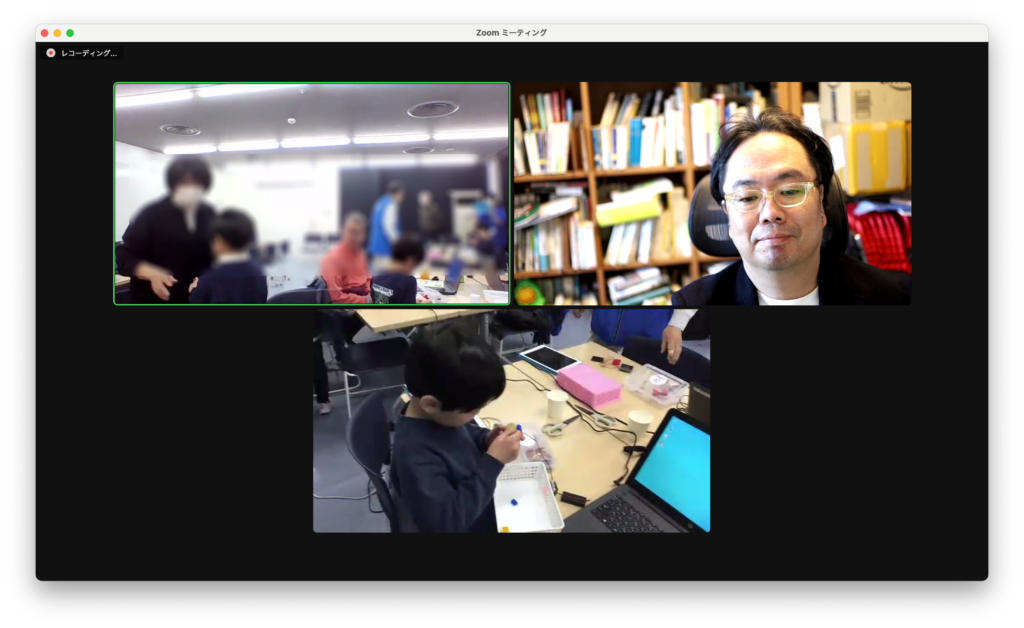

On December 23, we held a remote workshop at the Hamagin Children’s Space Science Museum. This time, we used a micro:bit with an expansion board (chobitto board), a.k.a. chobitto, to make toys that work with computers and programs (to make it easier to understand, the name needs to be decided).

We recruited participants for two workshops, one in the morning and one in the afternoon, and most of them were first-graders, with a few third- and fourth-graders (first- and second-graders were asked to participate with their parents this time).

We had originally planned to use a laptop PC to program with Microbit More, a Scratch-based programming environment, but after checking the composition of the participants, we decided to try the chobitto version of Programmable Battery In the chobitto version, five on/off patterns are determined by pressing the A and B buttons (A and B for movement, A+B for decision and release).

Children and parents who wanted to try programming with a laptop computer were given the opportunity to take their time and enjoy programming with Microbit More, while participants who wanted to first enjoy making computer-operated toys were given the opportunity to use the chobitto version of Programmable Battery for participants who wanted to enjoy making computer-operated toys first.

Although we still need to consider the management of the workshop, such as explaining the tools to the participants, we felt through the workshop that we would like to continue to consider having the participants choose the tools according to their experience.

In workshops where time is limited, activities are inevitably limited to only one tool. Considering the preparation of tools and materials and support for participants, it is true that it is easier to manage a workshop if activities are limited to tools. However, if we go back to the most important aspect of a workshop, “creating something that participants are interested in,” tools may not be the first thing we should focus on in a workshop.

“Learners are particularly likely to make new ideas when they are actively engaged in making some type of external artifact ‒

be it a robot, a poem, a sand castle, or a computer program ‒ which they can reflect upon and share with others.

Constructionism involves two intertwined type of construction; the construction of knowledge in the context of building personally

meaningful artifacts.”

Kafai, Y.B. & Resnick, M. (1996) “Constructionism in Practice : Designing, Thinking, and Learning in A Digital World”

Once again, I would like to go back to the starting point of constructionism and reconstruct the workshop.

My own knowledge of workshops may also be remade each time through each workshop.

Whether remotely or in person, I learn from the people I run the workshop with and through the workshop. This time, I learned from the people at the Hamagin Children’s Space Science Museum about their attitude and techniques of listening closely to the children and providing support.

I wanted to think together with the participants rather than immediately give them the answers, but it was difficult to find the right time to support them remotely, and I think I was too direct in my support.

The workshop also made me think about how to support children more carefully without using the remote as an excuse.

I am looking forward to the next workshop at the Hamagin Children’s Space Science Museum.